Sunday, February 28, 2010

Reflection: The Martian Chronicles

Saturday, February 27, 2010

Reflection: The Martian Chronicles

That's right, I capitalized it. Because that's how we idealize it in our culture, isn't it? And when Spender's going on his rant that we didn't put a hot dog stand at Karnak because it wasn't economically feasible, it struck me that we will, however, basically eradicate a mountain in the Black Hills of South Dakota so that people can look at faces of presidents etched in stone. Most of the people who leave Earth in this book to get to Mars are looking for a New Start, a New Way of Life, Freedom, the Opportunity to Succeed...What does that sound like? I'm sure we'll get more into this while reading Manifest Destiny, but I also noticed that we kept accidentally inserting the word "smallpox" into our conversation about the Martians, even though they hypothetically died of chicken pox. Thank you, American history.

Thursday, February 25, 2010

Telepathy, phantoms and the limitless differences of alien life

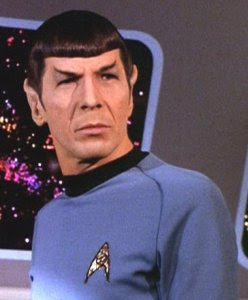

I’d like to address Yaniv’s substantive on the Martian Chronicles and add some additional commentary of my own. For one, because we have not experienced any other sentient beings, humanity’s conception of what other aliens could resemble is somewhat two dimensional. Our conception of aliens consists mainly of humanoids who fail to deviate far from human physiology. Antagonistic aliens are also often portrayed as insect-like and aesthetically unappealing. However, humans fail to realize that what is aesthetic is relative and subjective. An alien with red eyes and fangs is just as likely to be benevolent as an oversexed feminine humanoid. This form of thinking also applies to the natural processes of aliens. What may be unthinkable on Earth may be the norm on other planets. For example, on an alien planet water might be acidic to life forms that have evolved to survive in other liquids. I’d like to bring this logic to the Martian’s phantoms and telepathy. In one of the vignettes the Martians were able to take shapes to impersonate humans in order to kill one of the expeditions. Shapeshifting may simply be an evolved form of a chameleon’s ability to change colors. Who are we to say what millions of years of evolution could do? How the Martians could access these memories is another question. I would hypothesize that it was based in the Martians innate telepathic abilities. Telepathy is not a farfetched concept. The human body is controlled by electrical impulses from the brain and generates its’ own energy aura. Studies have shown that intense emotions, concentration or even meditation can greatly affect and augment the human body’s electrical composition. Just as different species have different organs to see various spectrums of light, why cannot an alien have an organ that enables it to manipulate different forms of energy? In addition to this, if energy can be used to control a body, could it not also be used to manipulate the mind? On a side note, if you wish to read about energy control of the body, you can google research on the creation of cybernetic animals with chips that release manipulating electrical impulses. Concerning the phantoms, if the body has an energy aura and the Martians have the ability to control forms of energy, is it not possible that even after the physical body has been destroyed that the Martians could exist in another form? Star Trek also uses the explanation of energy as the rationale behind telepathy. In the series telepathy is based on psionic fields, which are a different “spectrum of energy” that only certain species can control. On the subject of the lack of a Martian government, there is a reference in one vignette to the fact that some of the Martians weapons were left over from long ago wars. Perhaps the Martians had evolved socially to the point where a state was not necessary. On the subject of why the Martians attacked, the first attack was based on the fear of infidelity… thereby making it a crime of passion and perhaps not based in rationality. The second attack was based on misunderstanding. Concerning the third, I am not certain but I believe the Martians’ ability of precognition may have made them realize that death, from the plague, was coming and that they should fight back.

Sunday, February 21, 2010

Substantive: The Martian Chronicles

The Martian Chronicles stands in my mind as one of the most fascinating studies of alien existence and colonization. It is replete with that nostalgic charm for which Bradbury is so famed, but while certain aspects of this book could be considered Dandelion Wine-light, there is so much more to it than a young boy’s fantasy turned science fiction novel. The very first time we meet the Martians, they are, with a few embellishments, essentially very close to human. Ylla is trapped in an unhappy marriage, they talk of socializing with the neighbors, going to the city, etc. Her husband’s reaction to her dreams of the arriving Earthmen is to react jealously and kill them.

In contrast to something like Speaker, where we explicitly get the notion of This species is not human and cannot be treated as such beaten over our heads, the nature of the Martians and Earthling colonialism is significantly less cut-and-dry. For instance, in the story where the Second Expedition arrives on Mars, the Martians assume they are mentally ill or telepathic hallucinations, and eventually wind up shooting them in apparent self-defense. Also in the Third Expedition, when the Americans are essentially lured into what they see as their childhood homes, only to be murdered and buried. While these are both acts of self-defense (and at least in the first case an argument can be made for a cultural idiom in which telepathic hallucination is an aberration but part of society), the human beings in both cases are not explicit threats, only potential ones. While we can discuss the impending imperialism of this arrival as a terrifying reality, the fact of the matter is that the Martians, at least in the earlier parts of the book, exhibit a frightening method of “shoot first, ask questions later” and in fact lure the Earthlings to their deaths. This involves deliberation, which is, at least in the

And yet, we find later that the Martians have essentially been wiped out, turned into ghosts, by Earthborn illnesses, much in the way of War of the Worlds—and yet instead of the odd sense of relief and triumph that inhabits the final chapters of Wells, we get the sense of this incredible, majestic civilization suddenly wiped out, implying that Earthling and American imperialism—and does it strike anyone else as peculiar that all these settlers seem to be American?—ruins everything beautiful. It reminded, poignantly, of Watchmen (particularly the graphic novel, but the film adaptation is mostly faithful to this), when Dr. Manhattan, standing on the surface of Mars, refuses Laurie’s insistence on the merits of human life. Please forgive that this is from the movie, as I have currently lent out my copy of the book:

"In my opinion, the existence of life is a highly overrated phenomenon. Just look around you. Mars gets along perfectly well without so much as a microorganism. Here, it's a constantly changing topographical map flowing and shifting around the pole in ripples ten thousand years wide. So tell me: how would all of this be greatly improved by an oil pipeline?"

The Mars in which the Martians once lived is now exquisitely desolate and empty. And then in come these settlers, pioneers, to turn everything into Earth 2.0. And then, in the end, everybody goes back to Earth due to the impending nuclear war, and now Mars, which once had a thriving civilization, is almost completely empty.

Thursday, February 18, 2010

The Martian Chronicles: Cyborgs, Colonies, and Miscommunication

The Martian Chronicles raises a number of questions, not just about contact with extraterrestrials, but sentience, colonization, communication and human nature itself. The cyborgs in the chronicles are able to mimic a human personality almost flawlessly. However, some of them are also self aware that they are machines, such as the wife and children of the crewman, thereby making them independent of their programming. Does this level of consciousness make an entity sentient? Would a cyborg technically be an individual like you or I? If so, would cyborgs have the same rights as a living being? Would it be ethical to force thinking rational beings to do work? If we did, due to their artificial intelligence and mechanical strength, cyborgs would be very difficult to control or fight. It is even difficult to beat an AI opponent In Mario Tennis... imagine what a machine bread for war could do. Although cyborgs could be programmed into submissiveness, this cannot be achieved without compromising their creativity and effectiveness. Eventually enslavement might lead to a violent uprising such as in Battlestar Galactica or Mass Effect. This is especially because we would most likely use machines for nefarious purposes such as war and sexual pleasure; as we do today, though on a limited scale. Based on the fickle and often self destructive nature of humans, we may also be considered more of a liability than an ally.

One of the more loaded vignettes that intrigued me was “Way in the Middle of the Air.” It seems consistent with history that the African Americans would jouney to Mars as most oppressed minorities seem to be the vanguard of colonies. Even with the foundation of American we can see a number of religious and ethnic minorities fleeing to the new world.This tend proceeded even to the turn of the 20th Century, when there was an endless stream of boats carrying oppressed peoples to America. I also enjoyed and commend Bradbury’s commentary on racial discrimination in the South even before the issue became prevalent in American media. One story that I was doubtful about though was the one in which humans return from Mars to Earth in order to aid during a catastrophic atomic war. I feel that most people would not risk their families and personal security to go boldly into an unknown situation. It also seems illogical, though noble, to return to a place where you just fled from to confront the issue you were fleeing. I do believe that some people would return though to aid their fellow humans, but not humanity as a whole. To make a modern day comparison, Jewish people return to Israel, despite its’ dangers, in order to reclaim their heritage and strengthen the Israeli community. I do agree with Bradbury, though, that an object such as a metallic tube might be misconstrued as a weapon to either humans or aliens and lead to violence. In an alien culture a gun shaped object might actually have no meaning or perhaps even a positive one, such as a medicine dispenser. However, an object as innocent as a baseball may be reminiscent of a grenade to another species. This makes inter-species communication extremely delicate and complex.

Wednesday, February 17, 2010

Gender and LGBT themes in Science Fiction

Sexuality... the final frontier. Sexuality and gender rights are something humanity grapples with to this day. Of course you may say to yourself that in America women have been emancipated and homosexuals are free to do whatever and whomever they like. Granted the US is in a better state than Saudi Arabia where homosexuals are executed or in parts of Africa where girls have their genitals mutilated. However, America has not come as far as it could have. Only a few years ago a woman was fired by a Christian fundamentalist organization for… being a woman. Only seven years ago were homosexual acts banned in US states. Despite recent legal gains, there still remain stigmas and discrimination that cannot be removed by any law. Daily women are halted by the class ceiling or homosexuals are disowned by their families. If this is us today, where will we be in the future, and what does science fiction predict?

A great deal of science fiction portrays gender equality in the future. In the game Mass Effect the character’s crews’ professional soldier is a female that has very feminine characteristics. If the player chooses a female character their avatar is treated with the same respect as a male character. In Mass Effect 2 there are multiple strong female characters in the game who exhibit feminine characteristics and who are extremely courageous and have exceptional martial prowess. Star Trek was very influential in breaking gender stereotypes by having strong female characters, such as Uhura, who was one of the black female characters on television. The Next Generation continues this trend by having three strong female main characters, including Tasha Yar as security chief. This leads to the question of whether humanity will gradually evolve to be gender blind and continue to gradually progress throughout the centuries? Or will the changing nature of warfare allow women a greater role in conflicts? This is not to say that women cannot perform as well as men. I personally believe that if a woman wishes to fight in a conflict, she should be able to. However, it is a general conception that females should not fight in modern wars. On the other hand, there are works such as “The Handmaiden’s Tale,” which although a feministpiece, portrays a totalitarian world where traditional values suppress women in a disaster stricken world. Would the need to reproduce for war, for survival, or to colonize new worlds abet the repression of women in the future?

LGBT equality seems to be less touched upon in mainstream science fiction, although there are subgenres of homosexual science fiction. Star Trek, although a forerunner in women rights and multiculturalism, shied away from LGBT issues. However, there has was one episode of Deep Space Nine that featured a female marriage and kiss. Mass Effect on the other hand was banned in multiple nations for having a lesbian sex scene between a human and a feminine alien. These examples seem to reflect the common belief in Western society that lesbianism is more acceptable than homosexuality in males. One show that has broken barriers is Torchwood, the characters of which are mainly bisexual or omnisexual. The show is famous for a passionate kiss between the main protagonist and a character played by James Marsters, who was Spike in Buffy the Vampire Slayer. As we encounter other species, we may find that they have four genders or reproduce in a way completely unlike ours. Perhaps this will open humanity’s eyes to new horizons of acceptance.

Substantive: The Martian Chronicles

Tuesday, February 16, 2010

Reflection: Speaker for the Dead

Sunday, February 14, 2010

Reflection: Speaker for the Dead

We have a tendency to forget, reading this book (and Ender tends to forget as well) that Jane is not human. She looks human and acts human, within the context of her computer existence, as a means of facilitating communication with Ender. Her nature, and the way others treat her, reminds me greatly of what we were discussing while reading Concept of the Political--her power and abilities are so far above the realm of human experience, and so comprehensive, that there is no choice in the human-Jane relationship but to consider her a friend, because to consider her an enemy would be preposterous. She is the ansible, she dwells inside the philotic web, and as such everything that humankind is completely dependent on is dependent on her.

And yet when Ender switches off his comm, it hurts her. Deeply, on an emotional level. He does it as though chastening a naughty child, but as she has devoted so much of her attention and her understanding to Ender-as-father-figure, it's like losing contact with a parent. Losing part of herself. And though she recovers, eventually, time for her passes much differently than for humans, and by the time he switches it back on she has undergone the equivalent of a million years of suffering and recovery. Because Jane puts on this facade of humanity, Ender doesn't recognize, as he does with the Hive Queen, that she is alien or different, and that is a problem. If we perceive Jane as a person, and not merely as a computer program (and she is a person) then we must treat her as ramen or varelse because her thoughts and experiences are too different from ours to treat her as a framling.

Thursday, February 11, 2010

Reflection:Concept of the Political

The question of whether or not humans would actually pursue a path of friendship is another question. Humanity’s history of colonialism, genocide and racism would indicate otherwise. I myself have questioned how far we have advanced in light of Darfur and Rwanda. However, humanity has gained a greater sense of objectivity and enlightenment; otherwise this discussion would not be taking place. The fact also remains that humanity is not uniform in mentality or societal values. Therefore, to say one single human response would occur is improbable. Personally, I would strive for peace… but would not be surprised if a ship hovering over DC was shot down. Such is the human condition.

Substantive: Speaker For the Dead

In some respects I believe that the piggies should have been quarantined. Unlike the war between the Buggers and the Humans, the piggies were a legitimate threat to all life in the universe, not simply to human territory. The Descolada the piggies carried would wipe out life on any planet it was released on. The piggies could actually utilize this as a form of unconventional warfare and any species, any army and any force would be woe to resist them. Although I am very supported for self-determination, this is a specific scenario where growth should be limited for the greater good, not just for one species but for all of those in the universe. To commit another xenocide, however, would be unnecessary if the piggies’ technological growth could be kept under control. Xenobiologists could also work on a cure to the Descolada in order to enable the piggies to expand and grow freely. Despite this, I believe it was naïve for Ender and the colonists to risk so much in order to modernize the piggies and I do not see how the information about the Descolada would ensure the safety of the colony. Rather, it would put it in greater peril.

Tuesday, February 9, 2010

Substantive: Speaker for the Dead

Ah, Speaker for the Dead. Is it really a sequel for Ender's Game? The story behind the book seems to give the reader a little doubt as to whether Ender actually belongs on Lusitania in the first place. Maybe Card just couldn't manage to have the book stand on its own without the complex character of Ender? But then again, Andrew Wiggin from Speaker is hardly the Andrew Wiggin from Ender's Game. We need to tackle the complex issues brought into Speaker that are derived from Ender separately from new themes and statements made by the book sans Ender and his past. But, at the same time, Ender's presence informs and illuminates the issues brought forth in Speaker. To do a complete analysis of themes of alien and the other in Card's second Ender novel, these two aspects need to be individually considered, and then in some ways, combined.

Ah, Speaker for the Dead. Is it really a sequel for Ender's Game? The story behind the book seems to give the reader a little doubt as to whether Ender actually belongs on Lusitania in the first place. Maybe Card just couldn't manage to have the book stand on its own without the complex character of Ender? But then again, Andrew Wiggin from Speaker is hardly the Andrew Wiggin from Ender's Game. We need to tackle the complex issues brought into Speaker that are derived from Ender separately from new themes and statements made by the book sans Ender and his past. But, at the same time, Ender's presence informs and illuminates the issues brought forth in Speaker. To do a complete analysis of themes of alien and the other in Card's second Ender novel, these two aspects need to be individually considered, and then in some ways, combined.Monday, February 8, 2010

Substantive: Speaker for the Dead

I remember when we were talking in class about how, in War of the Worlds, Wells essentially takes the triumph and the victory away from mankind. I feel as if, in order to create a better world, Ender has deliberately sabotaged his own reputation. In writing The Hive Queen and the Hegemon he condemns his hero-self to millennia of ignominy because, if humanity were to consider itself triumphant, flush in the victory of having eradicated an alien species, the next would be disposed of in the same way, and for the same reasons. He also does so in the hopes that, when the Hive Queen is finally restored, she will be greeted by a universe explained into understanding by Ender's book.

This is a very different world in which to introduce a new alien species, and it shows. And yet, I'm not sure that humanity learned the right lessons from the Bugger Wars. Ender makes the point of explaining that the reason for this policy of non-interference is not, as might be imagined, a policy of tolerance engendered by his book, but a policy designed to prevent the exact kind of technological advancement that enabled the humans to defeat the buggers in the first place. It is the scientists who see these pequeninos as people who really treat them as ramen, in terms of Valentine's Icelandic-sounding hierarchy, and the government who treats them as children or varelse. It's almost as if the government is refusing to acknowledge them as equals, on an equal political plane, but treat them as some kind of endangered species. As an animal, as opposed to an alien. The result of this is, of course, that the pequeninos learn significantly more about humanity than they do about them.

There is a small hint of Ender's influence, though. When the xenologers are killed, there is no retribution from Starways Congress or the government. I could feel Ender's thoughts behind this in some way: What may be considered a travesty by us may be something completely different to them, in the same way that the buggers understanding of death and murder was entirely different from humanity's at the beginning of the Bugger Wars. The piggies a) believe that these people that they "kill" are anesthetized; b) do not realize that tears are a sign of human suffering; and c) reserve the ritual dismemberment for their most honored citizens. These are things that Ender notices almost immediately as meaning that their notions of death are different, but is this because he is inherently empathic or because he's seen it all before? What I thought immediately of was ethnocentrism. These xenologers were so absorbed in their own culture that even venturing into other ideas (like realizing that the trees were actually alive, and not totemic) was almost beyond their comprehension.

Reflection: The Concept of the Political

Saturday, February 6, 2010

Reflection: Concept of the Political

I apologize for having begun this reflection with something fundamentally a-scifi, but it was brooding at the forefront of my mind for almost, if not the entirety of the class. It also made me think about what classifies a human being. If we say that humanity cannot, by definition, really fight itself--and I believe Schmitt does make that contention--then humanity as a political entity can exist by defining other groups as being outside of the realm of humanity. I won't go back to the example of Nazi Germany here; instead I'll choose to focus on something like Dune, where, by identifying the Fremen as subhuman, the Emperor and the Harkonnen can excuse what is essentially an economic takeover. But, remember, most just wars are entirely political machinations. Everything can be justified politically--and this is something we will definitely see in a more extreme context in Speaker for the Dead.

Wednesday, February 3, 2010

Substantive on "The Concept of the Political"

In terms of Schmitt’s “other,” I would argue that we do not need another species to have a perfect “other” and that an alien species may actually be similar to humans and thus cannot be a perfect “other.” Humans have a tendency to dehumanize their opponents to the point that they are no longer humans. Even as children we call certain people “bullies” and feel little remorse if they get in trouble or are berated by others. If someone fights back and hurts bully its’ ok as they are evil and they deserve it because they’re a mean bully. If a terrorist is killed, do we feel remorse? Do we view them as human? We might feel more disgust if we witnessed a sheep being killed more than a member of the Taliban. I feel that even within humanity we humans may view others almost as aliens or another species. On the other hand, certain alien species may be very “human.” Extraterrestrials may be humanoids who talk like humans, think like humans and act like humans. If this were to happen, they could not be a perfect “other” to be antagonized. However, in films such as Starship Troopers, where the aliens are seen as non-sentient insects, extraterrestrials can serve as good “others.” In the film, the threat of insect attacks helps keep an authoritarian federation strong, despite several defeats. The Formics in Ender’s Game also serve a similar purpose, and once they have been defeated the alliance in the plot falls into disarray. I’d like to reiterate a point I made in another blog post. There can exist alliances for the betterment of humanity that are not formed around a “friend-enemy” dynamic. Today the UN does charitable work throughout the world and the EU has interconnected many countries together to the point that war is considered to be impossible between Western European nations. Our future does not need to be characterized by an authoritarian federation. Instead we can strive for an organization like the Federation from Star Trek, which is a viable goal to strive for… a political entity based on self improvement and peaceful cooperation with others.

Tuesday, February 2, 2010

Substantive: The Concept of the Political

In this post, I want to continue the application of Schmitt to Orson Scott Card's Ender's Game. Last post I covered what I saw as the application of Schmitt's political philosophy to the politics being played out on Earth as Ender was attending battle school in the asteroid belt. Principle to the politics of of post-Bugger Earth were the internet (I use internet in the context of what we would understand the concept to be, not necessarily what Card 100% envisioned) personalities of Locke and Demosthenes. As we understand from some of the interspersed chapters and the final chapter of Ender's Game, the current political entities of Earth are united under the banner of defeating the Buggers, but on the brink of collapsing into infighting once again. In deft political maneuvering, Peter Wiggin utilizes his created personas to elevate himself to the position of Hegemon of Earth, essentially keeping Earth united. As opposed to the union of Earth during the Bugger wars, which very much so mimics Schmitt's friend-enemy political dynamic, Peter defies Schmitt's logic, and keeps humanity together via colonization practices, and steeling itself against future enemies, but not necessarily one present.

In this post, I want to continue the application of Schmitt to Orson Scott Card's Ender's Game. Last post I covered what I saw as the application of Schmitt's political philosophy to the politics being played out on Earth as Ender was attending battle school in the asteroid belt. Principle to the politics of of post-Bugger Earth were the internet (I use internet in the context of what we would understand the concept to be, not necessarily what Card 100% envisioned) personalities of Locke and Demosthenes. As we understand from some of the interspersed chapters and the final chapter of Ender's Game, the current political entities of Earth are united under the banner of defeating the Buggers, but on the brink of collapsing into infighting once again. In deft political maneuvering, Peter Wiggin utilizes his created personas to elevate himself to the position of Hegemon of Earth, essentially keeping Earth united. As opposed to the union of Earth during the Bugger wars, which very much so mimics Schmitt's friend-enemy political dynamic, Peter defies Schmitt's logic, and keeps humanity together via colonization practices, and steeling itself against future enemies, but not necessarily one present.